A Wifi Primer

Wifi’s become ubiquitous in the last 15 years. The first 802.11 wifi standard was published by the IEEE in 1997, and was specified with a maximum speed of 2 Mbps. Since then, we’ve seen astronomical increases in speed – the latest amendment to the wifi protocol, 802.11ac, has a theoretical upper speed of 3.39 Gbps to one station.

We talk a lot about Moore’s law doubling transistor density on processors every year, but we’ve seen a 1,700-fold increase in the information density we can squeeze out of the air!

An Overview

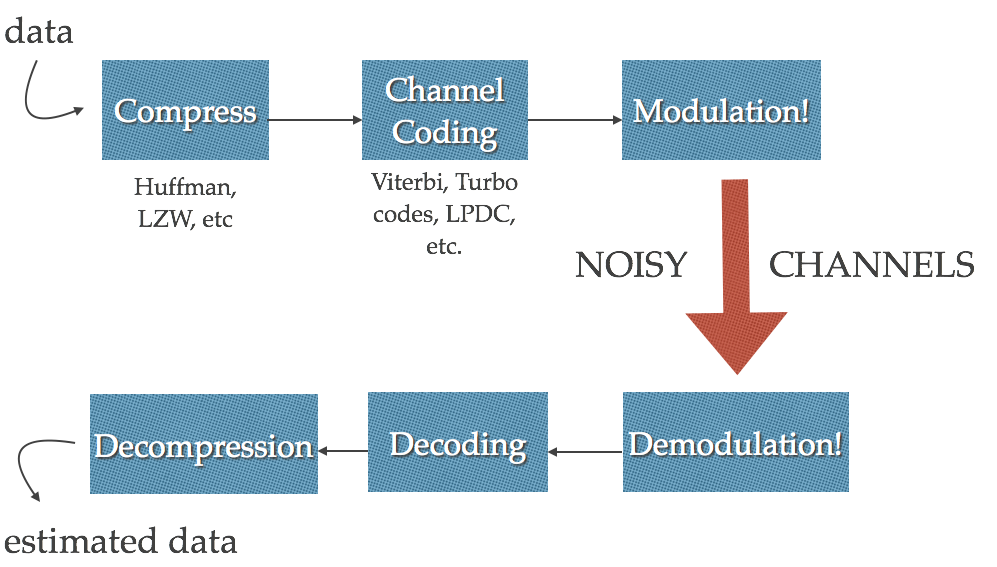

A 20,000-foot overview of how the whole process works:

Overview

-

First, the wireless transmitter attempts to compress the data. For an overview of how compression works, Julia’s blog post about gzip and Huffman codes is a great place to start!

-

Next, the transmitter adds redundancy to the compressed sequence with error-correcting codes. The simplest code imaginable is kind of a reverse compression – you repeat yourself 3 times, and the receiver takes the 2 that match. In reality, though, this isn’t quite the same as uncompressing the data – most error correcting codes rely on a series of increasingly complicated checksums to make this happen. If you’d like to read more about fancy error correcting codes, look into turbo codes or LPDC (low-density parity-check codes)! They’re pretty fancy. A warning – the Wikipedia pages are a little too full of jargon.

-

The transmitter then translates the series of bits generated into radio waves. This process is called modulation, and is one of the most dramatic ways that wifi protocols have gotten faster in the last few years.

-

Now that you have your radio waves, you can shoot them over the air! Keep in mind, though, that the air is noisy – we’re constantly surrounded by noise and interference, both from household appliances (microwave ovens are particularly noisome), and from other wifi routers in the vicinity.

Finally: Once the receiver gets the signal, it repeats the entire process in reverse, and hopefully has usable data! If not, the receiver can renegotiate how it’s sending the signal to be more robust to noise, and start the process again. This process of negotiating communication protocols is called link adaptation – in newer wifi protocols, there’s a code to determine which combination of encodings you’re using!

The compression and channel coding methods have optimized far enough that there’s not much room for improvement. However, there’s been a lot of advances in how the modulation and transmission techniques, partly due to advances in transmit/receive hardware sensitivity and an increase in computational ability.

The Shannon-Hartley Theorem

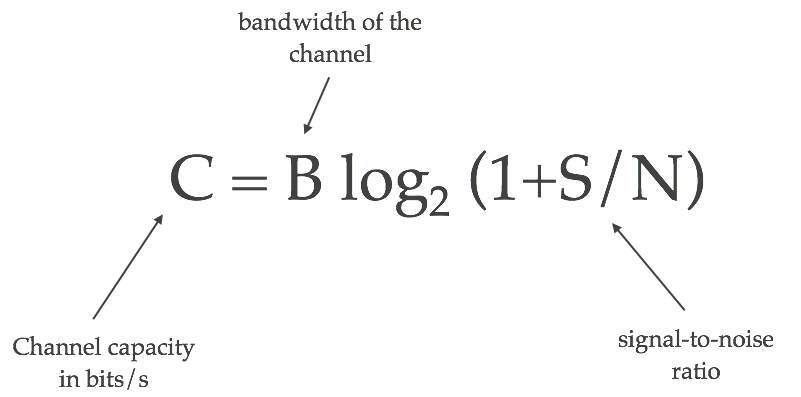

Why can’t you keep cramming more information into the air? There are a few fundamental physical limits that determine how much information a physical channel can hold, described by the Shannon-Hartley theorem.

This theorem says that, for a given degree of noise contamination, there is a maximum rate of digital data that we can communicate nearly error-free through the channel. (Note: the “error-free” comes from error-correcting codes!)

Shannon-Hartley theorem

The channel’s information capacity depends on the bandwidth of the channel you’re using – how many different frequencies you can talk over. It also depends on the signal-to-noise ratio, which is the ratio of the transmitted signal’s power to the background noise’s power. New wifi protocols have squeezed out more performance from both of these variables.

Tune in next week for more information about improving bandwidth performance with ~fancy~ modulation tricks (with no little thanks to more sensitive receivers!)